Plastic pollution has emerged as one of the most pressing environmental challenges of our time, threatening ecosystems, public health, and the sustainability of our planet. A pioneering study conducted by researchers at the University of Leeds reveals the staggering extent of plastic waste mismanagement on a global scale. The findings, encapsulated in the first-ever global plastics pollution inventory, emphasize the urgent need for effective waste management strategies. This article delves into the critical insights provided by the study while assessing the implications for policy, public health, and environmental preservation.

In an alarming revelation, the research indicates that an overwhelming 52 million metric tons of plastic products entered the environment in 2020 alone. To visualize this quantity, it is staggering enough to wrap this amount of plastic waste around the globe over 1,500 times. Such figures demand attention, particularly when it becomes clear that a considerable majority of this pollution—over two-thirds—is derived from uncollected rubbish. The study highlights that approximately 1.2 billion people, accounting for 15% of the global population, live without adequate waste management services. This statistic starkly illustrates a fundamental gap in what many consider an essential service.

Another critical facet addressed by the study is the uncontrolled burning of plastic waste. Approximately 30 million metric tons of plastic—representing 57% of all plastic pollution—were burned indiscriminately in homes and dumping grounds, often without environmental regulations. The act of burning plastic is not merely a disposal method; it leads to dire health consequences, which include neurodevelopmental issues, reproductive harm, and even birth defects. These outcomes are particularly devastating for marginalized communities who may lack alternatives due to insufficient waste collection systems.

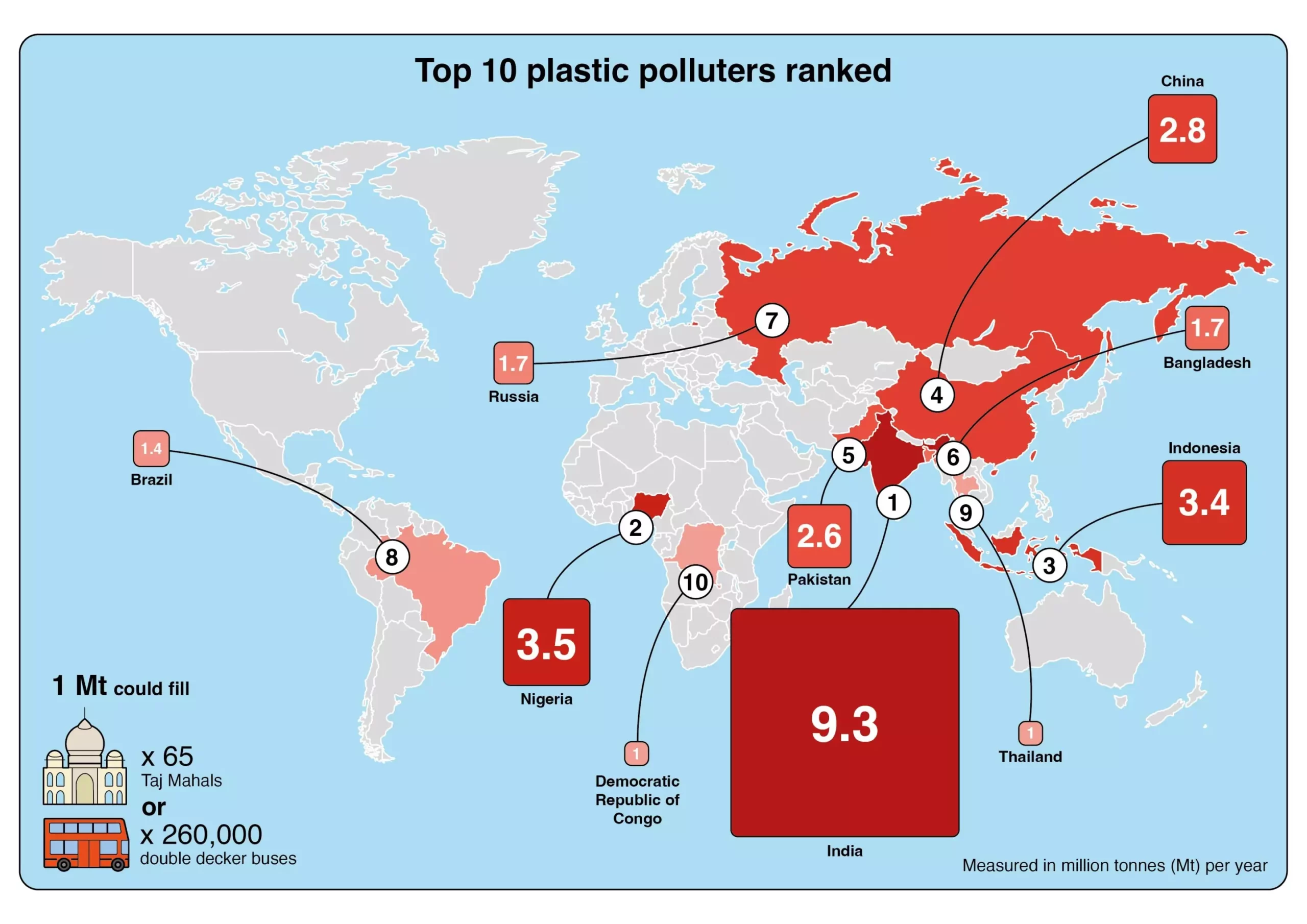

Initially, many models attributed the title of the largest contributor to plastic pollution to China. However, the latest study reveals a different narrative, with India taking the lead as the top contributor with 9.3 million metric tons of plastic waste introduced into the environment. Following India are Nigeria and Indonesia, contributing 3.5 million and 3.4 million metric tons, respectively. In a surprising turn, China ranks fourth, a shift attributed to recent improvements in waste management practices. This revelation reshapes our understanding of global plastic pollution and indicates that policymakers need to adjust their focus to reflect these new findings accurately.

The findings also expose a pronounced disparity between pollution levels in the Global North and South. Nations in the Global North, despite their high plastic consumption, have functional waste management systems that curtail macroplastic pollution. In contrast, many low and middle-income countries struggle with inadequate waste management infrastructure, exacerbating their plastic pollution issues. For instance, while Sub-Saharan Africa shows relatively low overall plastic pollution levels, per capita rates reveal troubling data—the region can average around 12 kilograms of plastic pollution for each person annually. Without immediate intervention, Sub-Saharan Africa risks becoming a significant source of plastic pollution in the coming decades, especially given its predicted population growth.

The implications of the University of Leeds study extend far beyond academia; the urgent need for effective waste management solutions is undeniable. The researchers argue that access to waste collection and disposal services should be viewed as a basic human right, akin to access to clean water and sanitation. Effective waste management is essential not only for diminishing plastic pollution but also for improving public health in disadvantaged communities.

To this end, there is a clear demand for global policymakers to collaborate on comprehensive frameworks aimed at reducing plastic waste. The researchers advocate for the establishment of a new, legally binding global ‘Plastics Treaty’ that would target sources of plastic pollution and hold nations accountable for their waste management practices.

One cannot overlook the urgency of addressing plastic pollution as both an environmental and human health crisis. The groundbreaking research from the University of Leeds serves as a clarion call, urging policymakers and communities alike to take action. Access to waste management programs must be prioritized, as uncollected waste poses a threat not solely to geographic areas but to the global ecosystem as a whole. As we navigate the future of plastic waste, we must recognize that alleviating this crisis requires concerted efforts on multiple fronts, from local governance to international treaties, to ensure a sustainable and healthier world for generations to come.