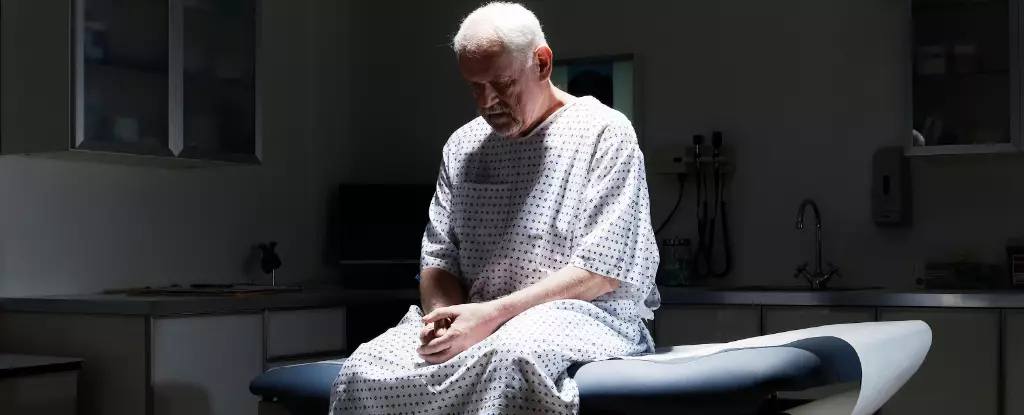

In recent years, humanity has made remarkable strides in increasing life expectancy. While this is a positive development, the underlying reality may not be as rosy as it appears. As the Mayo Clinic researchers have uncovered, the anticipated benefits of longer life are overshadowed by a concerning trend: the added years are often fraught with illness and disability. This article will delve into the implications of the widening gap between lifespan and healthspan, exploring the complex factors that contribute to this phenomenon and the pressing need for systemic change.

A comprehensive analysis covering 183 member nations of the World Health Organization (WHO) revealed alarming statistics. Although global life expectancy rose by 6.5 years from 2000 to 2019, the health-adjusted life expectancy increased by only 5.4 years, indicating that while people are living longer, fewer of those years are spent in good health. The Mayo Clinic’s findings showed that the burden of living with disability has also risen, with individuals across the globe facing an additional 9.6 years of life constrained by disease—a stark 13 percent increase since the start of the millennium.

Particular attention is warranted on the situation in the United States, which exhibits a markedly pronounced gap between lifespan and healthspan. Between 2000 and 2019, the life expectancy in the US increased by 1.5 years for women and 2.2 years for men. However, when accounting for healthy years lived, men only saw an increase of 0.6 years, while women saw no significant improvement from the figures recorded two decades prior. The implication is clear: if a woman in the US reaches the average life expectancy of 80.7 years, she can expect to spend more than 12 years grappling with health issues.

Researchers Garmany and Terzic point out that the growing disparity between these two metrics—lifespan and healthspan—is not merely a statistical anomaly; it represents a fundamental challenge that poses serious public health concerns. They highlight the urgent need to bridge this gap, underlining the broader implications for policies and healthcare systems designed to enhance the quality of life as populations age. Not only do women tend to have longer lifespans, but they also accumulate more years filled with chronic ailments like musculoskeletal disorders, signifying a need for gender-specific health interventions.

The WHO’s introduction of health life expectancy (HALE) aims to quantify these variations in health status among older adults, particularly post-60. The organization and the United Nations have embarked on a 10-year global action plan to redress the challenges faced by senior citizens, emphasizing the necessity of improved data measurement to rectify existing disparities.

Interestingly, the gap in lifespan and healthspan is not uniform across the globe. Data indicates that countries like the United States, Australia, and New Zealand struggle with significant gaps, whereas nations such as Lesotho and the Central African Republic have markedly smaller disparities. Such differences prompt an examination of the underlying social, economic, and healthcare frameworks that influence health outcomes in various regions.

Poor health indicators rooted in systemic issues exacerbate the burden of non-communicable diseases. The current state of public health in wealthier nations calls for introspection: the existing healthcare models often prioritize reactive treatment rather than proactive care that could lead to healthier aging.

Addressing the widening healthspan-lifespan gap requires targeted strategies aimed at enhancing the quality of life among aging populations. A multi-faceted approach, combining social, medical, and policy reforms, is essential. By prioritizing wellness-centric care systems, nations can begin to combat the pervasive trend of living longer yet unhealthier lives.

To intelligently tackle this issue, it is crucial to identify demographic groups suffering disproportionately from disability and disease during their later years. Successful interventions must not only improve lifespan but enrich the quality of those added years.

While advancements in longevity are an undeniable triumph of modern medicine and public health, the emerging data provokes serious questions about quality of life. As we move forward, it is imperative to align our healthcare systems with the goal of promoting both longevity and quality, ensuring that adding years to our lives also adds life to our years.