As the global climate crisis intensifies, recent findings reveal that the Arctic Ocean is losing its previously formidable capacity to sequester carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere. This deterioration is alarming, particularly when considering the implications of permafrost degradation and shoreline erosion, both driven by rising temperatures. A new study published in *Nature Climate Change* elucidates these trends, emphasizing the significant repercussions for atmospheric CO2 levels and, by extension, global climate stability.

Permafrost, the perennially frozen layer of soil, has long acted as a substantial carbon sink, sequestering approximately 2.5 times the amount of carbon currently held in the atmosphere. However, as temperatures rise at rates 3 to 4 times faster in the Arctic than the global average, the integrity of this frozen layer is compromised. Melting permafrost releases this stored carbon back into the atmosphere, a situation exacerbated by coastal erosion. The study’s lead author, David Nielsen, highlights the crucial finding that certain Arctic areas are emitting more carbon than they absorb, a trend that could mirror the carbon output seen from European cars in 2021 by the turn of the century.

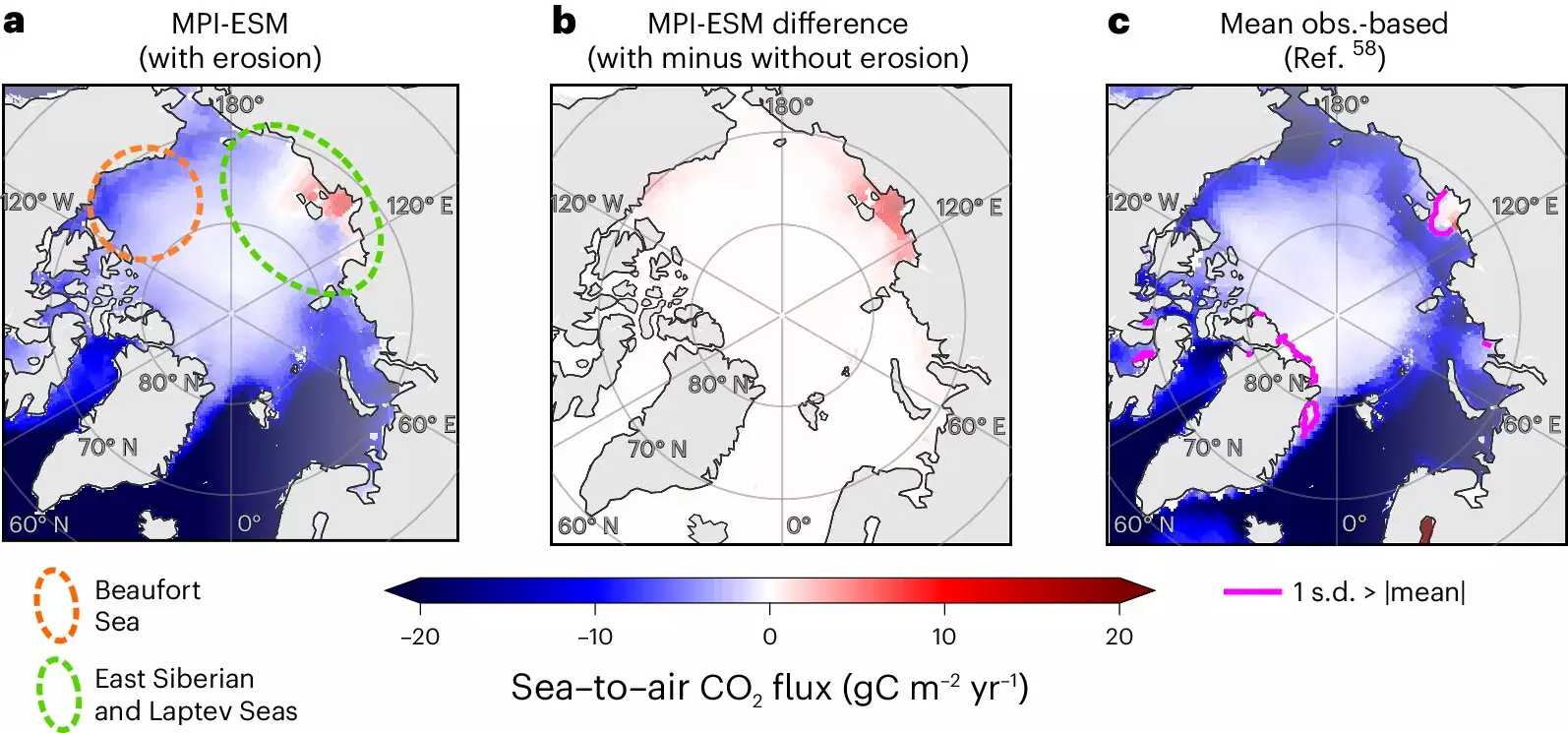

The erosion phenomenon is particularly pronounced in hotspots such as Drew Point in Alaska and the Mackenzie River Delta in Canada. As the permafrost thaws, the previously frozen soil becomes susceptible to coastal waves and storms, leading to the displacement of soil and carbon into the ocean. This cycle not only hinders the ocean’s absorption capacity but creates a feedback loop that further intensifies global warming.

The ramifications of this research extend beyond atmospheric chemistry; they bear severe implications for coastal communities grappling with the immediate impacts of climate change. With permafrost deterioration comes increased coastal erosion, which threatens local habitats and communities, such as Shishmaref in Alaska. The rising tides and stronger storms not only pose risks to infrastructure but also affect social structures and cultural heritage within these regions.

The decrease in the Arctic Ocean’s ability to act as a carbon sink may reduce its capacity to absorb over 14 million tons of CO2 annually by the end of the century, equating to the emissions produced by a significant number of vehicles. This alarming information underlines the urgent need for enhanced climate policies and strategies aimed at reducing human-caused emissions, which are the primary drivers of climate change.

While the study notes that the additional carbon emissions from permafrost erosion are not as significant as human emissions, representing only about 0.1% of the global total, the issues at hand are intricately connected. The continuous release of carbon due to permafrost thawing poses a critical challenge that science and policymakers must address. As Nielsen articulates, unless proactive measures are taken to mitigate fossil fuel usage and greenhouse gas emissions, this alarming trend will only accelerate, creating a compounding effect on Earth’s climate systems.

In light of these findings, it is essential for researchers and decision-makers to enhance their understanding of how these processes interact. Advancements in climate modeling and continued observational studies will be vital to charting the gravity of these changes.

The decline of the Arctic Ocean’s ability to absorb CO2 represents a critical juncture for climate action and environmental stewardship. The findings from this study serve as a stark reminder of the interconnected nature of Earth’s systems, emphasizing that localized changes can have far-reaching consequences. Expanding our knowledge of these dynamics is paramount for developing effective strategies to combat climate change on a global scale.

As humanity faces the multifaceted threats posed by climate change, the losses incurred in the Arctic may serve as a forewarning for the larger planetary repercussions that follow. A united effort to embrace renewable energy, reduce emissions, and protect vulnerable ecosystems is not just advisable but necessary for safeguarding the future of our planet. The Arctic may be experiencing change at an unprecedented rate, but our response can be equally robust if we act decisively today.