When a person’s heart abruptly ceases to beat, the window for effective intervention is alarmingly narrow; without prompt action, the chance of survival diminishes significantly. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) stands as a pivotal lifesaving technique that ensures the vital flow of blood and oxygen to the brain and other critical organs until professional medical help arrives. This process can mean the difference between life and death during a cardiac emergency. However, recent research exposes a troubling trend: bystanders are less likely to administer CPR when the victim is female. This discrepancy raises profound questions about societal biases, training practices, and ultimately, survival rates.

A study conducted in Australia, examining 4,491 instances of cardiac arrests from 2017 to 2019, found a significant gender gap in CPR application. Approximately 74% of men received CPR, compared to only 65% of women. The implications of these findings are disturbing, especially considering that cardiovascular diseases rank as the leading cause of death among women worldwide. Statistically, a woman suffering a cardiac arrest outside a hospital setting is 10% less likely to receive CPR than her male counterpart. This omission not only reflects a troubling gap in emergency response but may also contribute to the higher rates of complications, such as brain damage, faced by women post-cardiac arrest.

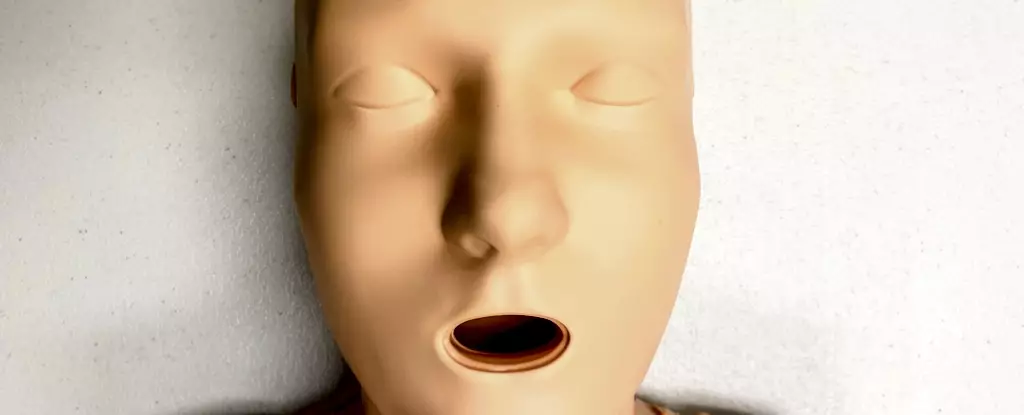

The nature of CPR training appears to play a foundational role in the disparities observed. Most CPR training resources predominantly use male-oriented training manikins, often devoid of anatomical features such as breasts. Recent research revealed that a staggering 95% of CPR training manikins are flat-chested, reaffirming the idea that most available manikins represent a male default. This lack of diversity in training resources may inadvertently shape bystander behavior, making it less likely for individuals to recognize or feel comfortable intervening in a cardiac emergency involving a woman.

The cultural perceptions surrounding gender and CPR are complex and multifaceted. Bystander apprehension about accusations of inappropriate behavior, discomfort with touching a woman’s body, or misconceptions regarding women’s frailty may contribute to a reluctance to perform CPR on female victims. In simulations that mimic real-life scenarios, a notable trend emerged: participants demonstrated less inclination to undress a female victim to facilitate resuscitation efforts. Such hesitations in the heat of the moment could result in dire consequences, highlighting the necessity for inclusive and comprehensive training that addresses these barriers.

The data doesn’t just point to a CPR training issue; it illuminates broader health disparities experienced by women, transgender individuals, and non-binary people. These groups often face dismissive attitudes regarding their health complaints, leading to misdiagnoses or delayed diagnoses for serious conditions. As the research indicates, this bias extends into critical emergency situations, where systemic inequalities can result in life-or-death outcomes. It reinforces the need for a societal shift toward greater inclusivity and understanding in health care and emergency response.

To bridge the gender gap in CPR responses, it is essential to modify both the training curriculum and the resources utilized. Training programs must incorporate a variety of manikin designs that reflect the anatomical diversity of the population, including models with breasts and different body types. This change ensures that participants become comfortable performing CPR on victims of all genders and body types. Furthermore, trainings should emphasize scenarios that provide learners with the skills and confidence needed to act decisively regardless of the victim’s gender.

The disparity in CPR application between men and women underscores the urgent need for reforms in training practices. Understanding that anatomical features do not alter CPR technique is crucial in fostering a compassionate and proactive response in emergencies. Training and education must evolve to address these biases, ensuring that every individual feels empowered to intervene in a life-threatening situation. Addressing these structural inequities can promote equitable health outcomes, ultimately saving lives. As we advocate for inclusivity in CPR training, we must also raise awareness about the risk women face when it comes to heart-related diseases—because every second counts, and every life deserves a chance to be saved.