Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), commonly recognized for causing cold sores, has ascended from its benign reputation to a more intimidating status as research reveals its potential to invade the brain and central nervous system. A collaborative study spearheaded by the University of Colorado and the University of Bourgogne in France has added significant insight into this phenomenon, offering crucial revelations about how HSV-1 infiltrates these vital areas and the subsequent impacts.

While HSV-1 has been documented to transmit to the central nervous system via the trigeminal and olfactory nerves, the mechanics of its dissemination within the brain remain murky. Neurologist Christy Niemeyer emphasized the urgency of untangling this viral intrusion, especially considering HSV-1’s recent links to neurodegenerative disorders, predominantly Alzheimer’s disease. The objective is not just to uncover the pathways of HSV-1 invasion but to pinpoint which brain regions bear the brunt of its effects. This fresh research represents an essential leap forward in decoding the enigmatic relationship between HSV-1 and cognitive decline.

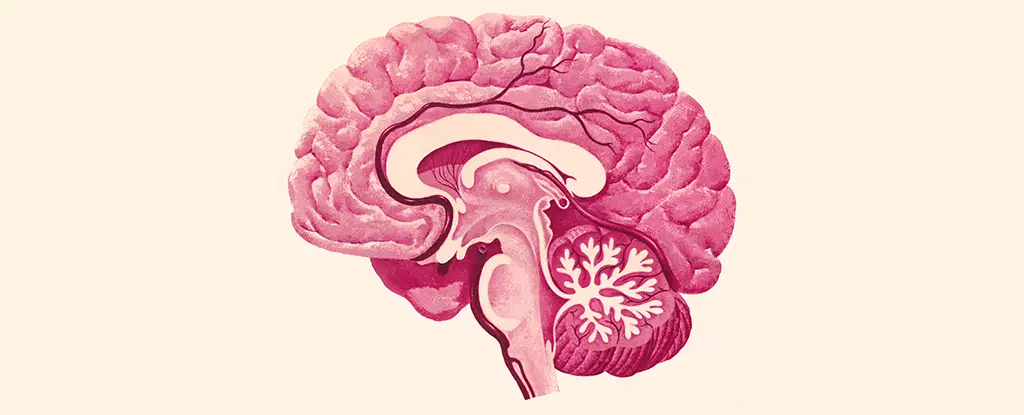

The research team’s exploration revealed that certain crucial areas of the brain are particularly susceptible to HSV-1. Notably, the brain stem, which governs vital functions such as heart rate and respiration, as well as the hypothalamus—a region instrumental in regulating sleep, mood, and appetite—demonstrated noticeable viral activity. In contrast, some regions remained relatively untouched, particularly the hippocampus, a structure central to memory and navigation, often implicated in Alzheimer’s pathology, and the cortex, associated with attention and memory processes.

This stark dichotomy in the central nervous system reveals something critical: while HSV-1 can secure a foothold in regions essential for survival and emotion, it appears to selectively ignore others that are closely tied to cognitive function. This observation begs the question of whether the virus’s footprint in the brain could create an environment conducive to long-term dysfunction, especially in regions pivotal for memory.

The study’s investigation into microglia—the brain’s resident immune cells—further illuminates the potential ramifications of HSV-1 infection. Upon exposure to the virus, these cells showed signs of inflammation, indicating an active immune response. Alarmingly, the microglial activity persisted even after the viral presence diminished, pointing toward a state of chronic inflammation that could persist indefinitely. Chronic inflammation is a well-documented precursor to various neurological disorders, raising concerns about the long-term effects of HSV-1 on brain health.

Despite not every case of HSV-1 leading to encephalitis—a severe condition marked by widespread brain inflammation—the potential for damage remains considerable, as highlighted by Niemeyer. The interplay between ongoing immune responses and the functioning of affected brain regions opens the door to worrying implications for overall cognitive health, especially regarding the development of neurodegenerative diseases.

Emerging evidence suggests that the relationship between HSV-1 and diseases such as Alzheimer’s could be deeper than previously understood. With recent studies hinting that the interplay between HSV-1 and persistent microglial inflammation may influence the onset and progression of Alzheimer’s, there is a compelling argument for researchers to investigate further how these factors interconnect. The regions that are vulnerable to both HSV-1 and the neurodegenerative processes could represent a crucial intersection that warrants more thorough exploration.

Niemeyer’s insights into chronic inflammation as a potential catalyst in the onset of neurodegenerative conditions underline the necessity for ongoing research into HSV-1’s role in brain health and disease. As we peel back the layers of this complex relationship, the findings from this study provide a foundation for future investigations aimed at deciphering how common viral infections may herald profound implications for mental wellbeing across populations.

The growing body of evidence accentuates the significance of understanding how HSV-1 functions, not just as a viral pathogen but as a potential contributor to widespread neurological decline. Further research in this domain may pave the way for novel therapeutic interventions that target these obscure but consequential interactions, thereby safeguarding cognitive health in vulnerable populations.